Last month, I reported on British newspaper The Sun’s feature about video game addiction, which sparked an interesting conversation in the comments. While some readers denounced the newspaper’s audacity to compare video game addiction to heroin addiction, a few were of the view that since The Sun is nothing short of a gossip-filled tabloid, it wasn’t worth paying mind to. The assumption here is that people should be smart enough to realize that the writer just wants attention, and that if someone is gullible enough to fall articles like these, then that’s his/her personal problem. This is where my opinion probably conflicts with a lot of fellow gamers’ because I personally believe that any writer who misleads the general public by presenting poorly stated facts or shoddy research should be held accountable for it.

Shortly after The Sun published its article likening video game addiction to heroin addiction, and declaring that British people have reached new levels of “mental health risk,” one of the professors quoted in the “research,” Dr. Mark Griffiths, took to Gamasutra to express his concerns about how his statements were misused by the author. He wrote that he provided the following quote, which was deliberately left out of the article:

Gaming addiction has become a real issue for the psychologists and medics over the last decade. The good news is that playing excessively doesn’t necessarily mean someone is addicted – the difference between a healthy excessive enthusiasm and an addiction is that healthy enthusiasms add to life whereas addiction takes away from it.

Dr. Griffiths also stated that the article was just a sensationalist piece and it was wrong of The Sun to publish it the way it did. I then took to Twitter to speak to the newspaper’s Deputy Head of Publishing (Tech and Video Games), Dan Silver, and exchanged a series of tweets with him. When I questioned him about the references to heroin, he justified it by saying that the article does not mention anything about similarities in “physiological” effects. When I asked him if he was aware of Dr. Griffiths denying that Britain was at risk like the article had suggested, he said, “@Zarmena Yes I do. That doesn’t have any bearing on whether video games are addictive in themselves though.” Notice the grasping of straws? He understandably doesn’t make any mention of Dr. Griffiths being misquoted in the article at all despite knowing about the professor’s rebuttal. I then asked Silver if he was admitting to letting the feature slip out without reviewing or if he actually believes in what was published, he simply responded by saying, “@Zarmena I’m not admitting anything at all.”

My main problem with letting this gibberish slip away is that it trivializes serious issues like mental illnesses and health risks. When I was younger, it was okay for children to be hyperactive, it was okay for us to run around and get into fights, it was okay for us to live and learn. With the advent of internet and media’s scare-mongering, I find that parents are confused and often clueless about what constitutes an “illness” or a “risk.” I’m not saying that creating awareness is a bad thing, but when there’s too much of an emphasis on something, people are bound to flip out over miniscule things. I can’t imagine how many children have had their consoles and video games taken away owing to articles such as these. And it would be wrong to assume that it doesn’t happen.

Even if we’re speaking of adults, exaggerating the severity of something has negative repercussions. We don’t need every other psychologist to be diagnosing people with assumed illnesses, and leading them into believing that something is “wrong” with them. Conversely, we also run the risk of leading people astray rather than addressing the root cause of a problem. Whenever there’s a tragic incident like the Sandy Hook massacre, the media specifically looks for links to things like violent movies and video games as if reporters are on a treasure hunt. As a result of this misreporting, people tend to overlook serious underlying causes that require urgent attention. I’m sure Adam Lanza was “shutting himself in the bedroom playing video games all day.” But we need to worry about what led him to “shut himself out,” not what specific video games he was playing.

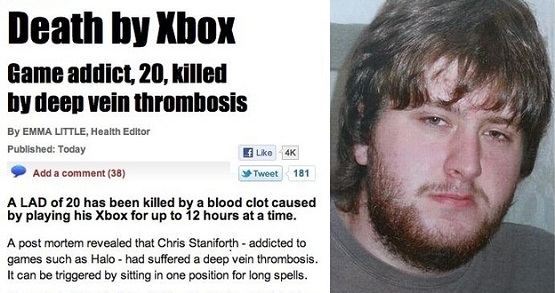

The belief that only “gullible” or “stupid” people fall for controversial articles, or any article published in a controversial tabloid, is a gross generalization. It doesn’t matter who goes on a witch-hunt against video games or where the article is published, people will read it, people will fall for it, and it will have a widespread impact at some point. I’m not saying that we can put an end to this because if it’s not video games, it’s something else; the world moves on. But I strongly believe that it is in the general public’s interest to have stricter regulations to deter people from writing on sensitive topics just for the sake of hits. Addiction and mental illnesses should be taken very seriously, not trivialized. Take, for instance, the case of Chris Staniforth, a 20-year old who died of blood clotting in 2011 from non-stop gaming. Instead of blaming his Xbox, emphasis should have been placed on the health risks that gaming marathons can pose.

If I was Dr. Griffiths, I’d be hiring a lawyer. After all, the privilege of suing for false reporting shouldn’t just be reserved for Kim Kardashian.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and should not be attributed to PlayStation LifeStyle as a whole.