I Gotta Believe

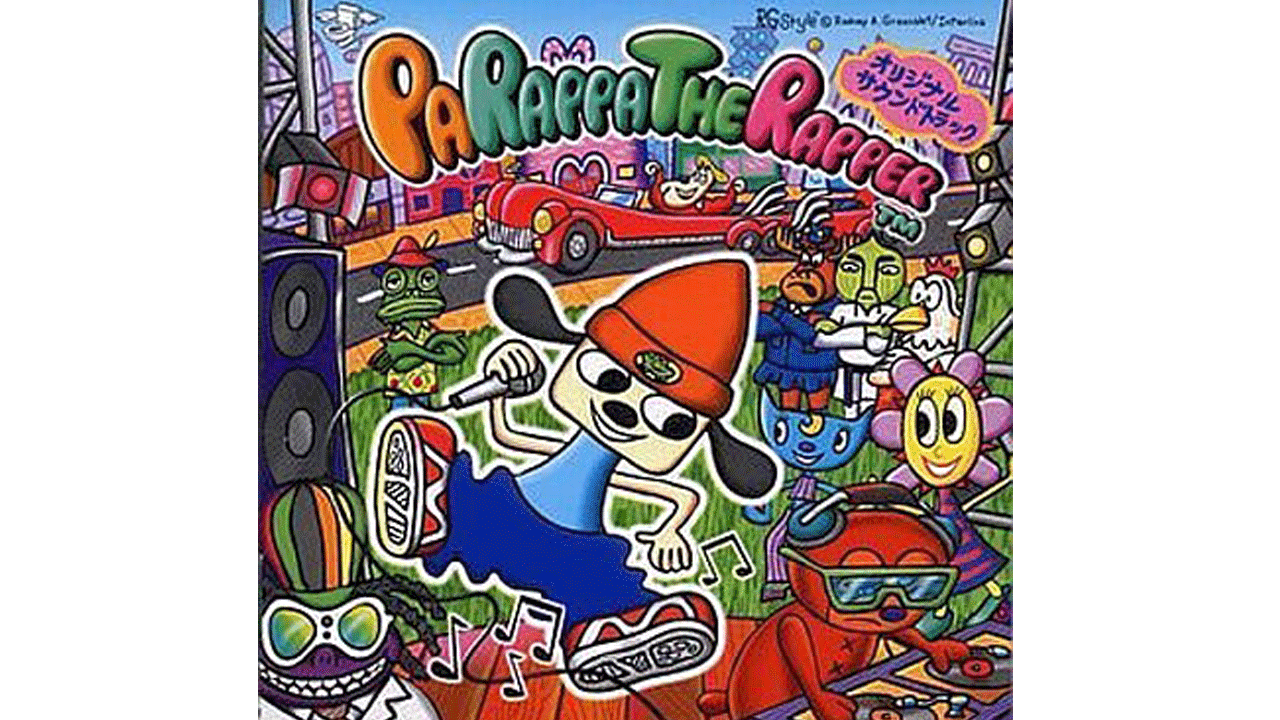

Wrapped in sparkling paper under my family’s Christmas tree sat the familiar squared outline of what was surely a PlayStation game case. It was 1997 and my brother tore the paper off likely expecting to see the familiar orange fur of Crash Bandicoot or the two triangles that represented Lara Croft at the time. Instead, he was met with a mess of color mashed into a 4.75-inch frame.

The cover image showcased a dog with an orange hat, blue shirt, and baggy jeans, holding a mic leaning in at an awkward angle in front of an array of bewildering characters – a flower, a cat, a moose, a karate master with an onion head.

It was a simple story about a rapping dog who liked a girl who looked like a flower. But more than that, it was about learning to believe in yourself. I played it. I loved it. I beat it and unlocked the ability to freestyle and played it some more. I memorized the lyrics. I bought it years later to play again on my PlayStation 2 and then again to play on my PS Vita. The world had charmed me like few games had at that time.

Don’t Get Cocky, It’s Gonna Get Rocky

For anyone raised on Rockband and Guitar Hero, PaRappa the Rapper’s simplistic button-timing mechanic might feel archaic. The game tasked players with timing button presses to the beat of the music. Each button press would allow PaRappa to spit a few more lyrical gems like, “In the rain or in the snow/Got the, got the funky flow.”

Admittedly, the mechanics of the game may have been its weakest point as timing button presses was more an act of intuition than properly lining up button prompts. But that kernel of an idea is why the titans of the genre today are able to release their PlayStation 4 and Xbox One treatments. They both owe a nod to gaming’s original emcee.

While PlayStation was responsible for launching countless franchises, it was PaRappa the Rapper that first introduced me to Sony’s penchant for all things quirky and offbeat. Not only did PaRappa exemplify the console’s habit for showcasing games taking creative risks, the paper-thin canine also introduced the modern rhythm game to its first generation of gamers.

It’s All in the Mind

PaRappa the Rapper was the brainchild of designer Masaya Matsuura and artist Rodney Greenblat and developed under Matsuura’s NanaOn-Sha company. Matsuura was heavily involved in headlining his band PSY S at the time – a Japanese hyper pop group. Greenblat was quite possibly at the opposite end of the creative spectrum working on children’s books. The pair met at a computer conference in the 90s and discovered they were coincidentally working in different groups inside Sony Japan. Matsuura was working on a rap-based video game that needed characters and a world. Greenblat jumped at the chance and the duo developed a strong working relationship that eventually birthed PaRappa the Rapper.

While the game’s visuals and musical flair are always the highlight of most conversations surrounding it, the most interesting aspect of the game was its genre – it didn’t have one yet. The musical rhythm genre hadn’t really been created as we know it today. This meant that not only was the team weighed down by the regular pressures of game design, they were also fumbling through uncharted territory, establishing the path companies like Harmonix and Neversoft would walk a decade later. Adding to that complexity was their choice to combine two socially maligned creative forces – video games and rap. The mixture should have imploded.

While Greenblat has stated the team never set out to create a genre or to combat the negative attitudes towards games and rap, PaRappa did both. And in forging a gaming genre, the team found success in an area no one else was looking.

He’s Got the Funky Flow

PaRappa the Rapper currently has a 92 on Metacritic. It sits tied for the twelfth best game on the original PlayStation. It has the same score as Final Fantasy VII and Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. It sits alongside megatons like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, Street Fighter Alpha 3, Gran Turismo, and Metal Gear Solid.

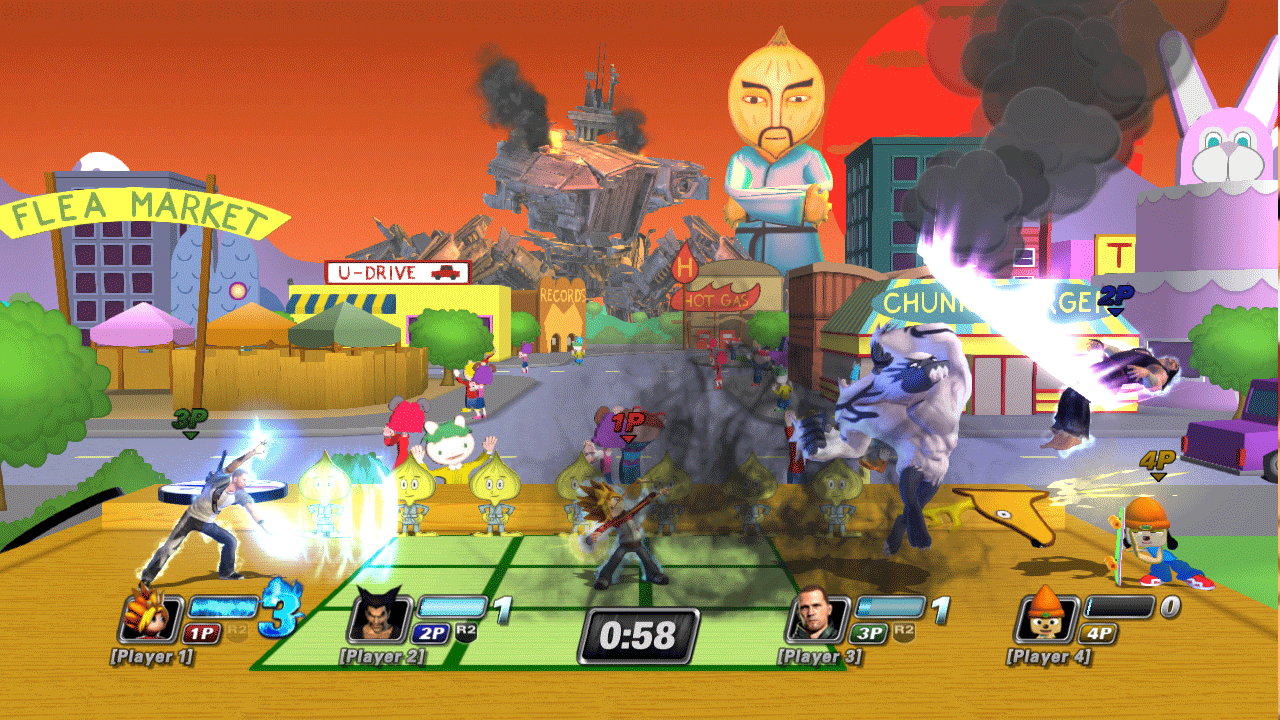

Combined with its re-release, it has sold approximately 1.5 million units. It spawned a spin-off in UmJammer Lammy starring a female, left-handed, guitar-playing lamb, a sequel in PaRappa the Rapper 2, an anime series, a seemingly infinite amount of merchandise, and the title character most recently appeared in PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale armed with all the punches and kicks Chop Chop Master Onion could teach him. The title also won countless design and musical achievement awards along the way.

But the game’s influence didn’t stop at the edge of its own success. After PaRappa proved music and games could be combined with great commercial and critical success, the genre was flooded by developers with equally unique concepts.

Titles like Space Channel 5 and Samba De Amigo tried to replicate the mascot rhythm success of PaRappa, while other developers began carving out subgenres. Amplitude added musical rhythm gameplay to the arcade driving experience while MTVs Music Generator took the musical concept literally, subtracting the gameplay, and creating a powerful mixing program for Microsoft’s original Xbox.

But the subgenre that earned the most success was the one that attempted to make the player the star of the show. We wanted to be PaRappa, not play as him.

Beatmania let us become an obnoxious DJ, Dance Dance Revolution let us become the weirdest dancer at any party ever, Singstar tricked us into thinking Karaoke was cool, and Guitar Hero and Rock Band allowed us to live the on-stage lives of our favourite coke-addled musical heroes (sans the coke).

It was an amazing time to be a fan of the genre.

But it was also too much, too fast. For better or worse, PaRappa had struck a chord; the industry obliterated it.

Ironically, the quest to make the player the star made the experiences less intimate. There were no stories being told in the space anymore; they had been replaced by star ratings, challenges, and downloadable song packs. These weren’t bad additions. In fact, it’s these additions that properly gamified the genre. The problem was that it has forever caused story-driven music games to feel less significant because they don’t include a plastic guitar and eight difficulty levels.

Fortunately, there’s always time to teach an old dog new tricks.

You Gotta Believe

PaRappa the Rapper is an undeniable icon. The character represents positivity in a community that isn’t always known for it and found success in an industry that most often rewards pessimism and destruction. More than anything, it represents gaming’s best feature – its ability to evolve and redefine itself as determined by players’ appetites.

The landscape for games that revolve around a musical hook has been quiet for some time now (eons in industry time) and the moment couldn’t be better for a triumphant return. The rise of indies and popularity of PlayStation Plus has created a safer place to take risks and a hungry market for reinvented gaming icons.

Of course, Sony has stated that rights issues make working with the property difficult, but that’s nothing new. Rumors are swirling in the dark corners of the Internet, alleged information leaks are linking well-known studios to the property, and excitement for a third PaRappa game is mounting.

Amplitude is back in 2015. Guitar Hero is back in 2015. Rock Band is back in 2015. It’s time for the OG of bottle cap selling to return.

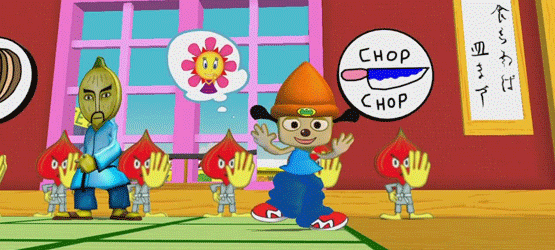

Inventing an Icon - PaRappa the Rapper

-

Kick!

PaRappa the Rapper Japanese Cover Art.

-

Punch!

PaRappa the Rapper Stage 1 - Chop Chop Master Onion

-

Chop!

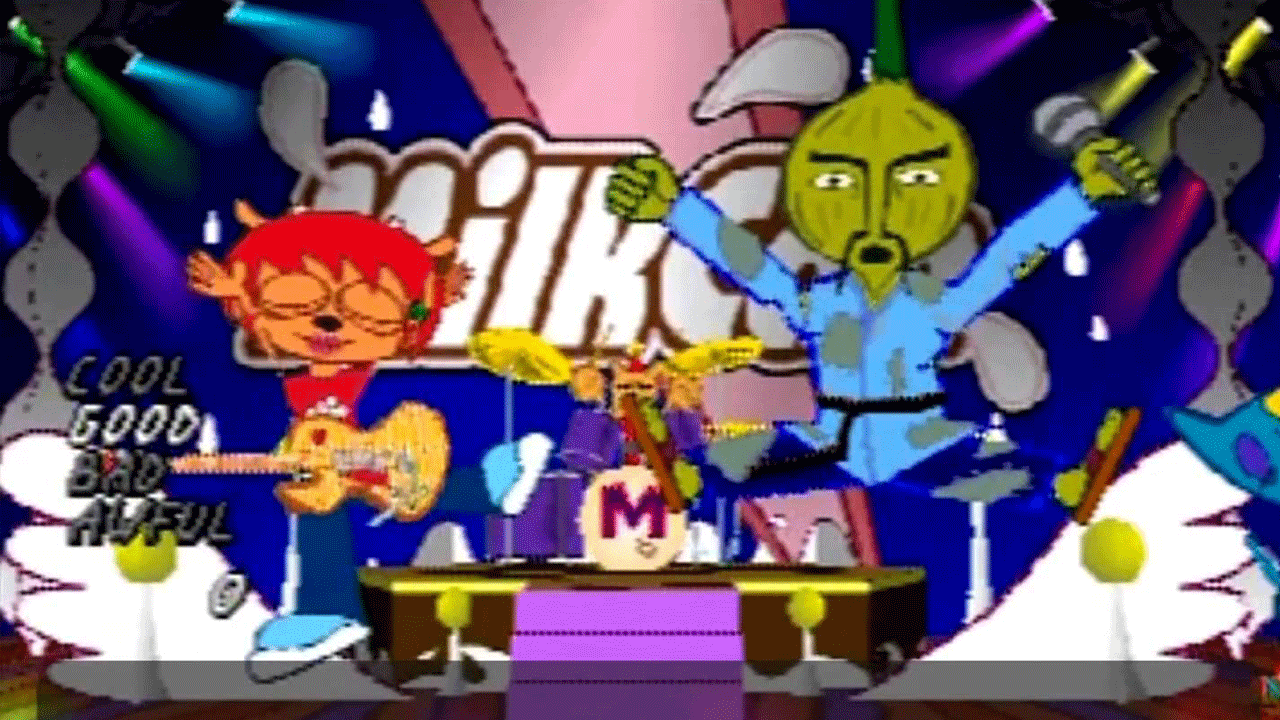

PaRappa the Rapper Stage 4 - Cheap Cheap the Cooking Chicken

-

Duck!

UmJammer Lammy had a host of returning characters like Chop Chop Master Onion.

-

Turn!

-

Pose!

The student becomes the master in PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale.