Draugen is a noir narrative exploration adventure (perhaps known to some as a “walking simulator” if you’d prefer the term). It’s a riveting mystery with an expertly woven story at its core. Taking place in the early 1900s, Edward and Lissie travel a long way from their Massachusets home to Graavik, a small village in western Norway, in search of Edward’s sister. Finding Graavik seemingly abandoned, Edward and Lissie must piece together both the town’s history and his sister’s footsteps in order to solve the mystery of both.

Ragnar Tørnquist is the director at Red Thread Games and the writer behind classics like Dreamfall Chapters, The Longest Journey, and The Secret World. Red Thread specifically is a term meaning an intertwined fate or destiny, an appropriate designation for the studio that made Draugen. Ragnar was kind enough to take some time to answer some of our questions about Draugen, writing the story, and what the studio plans to do next.

Draugen SPOILER WARNING

Be warned, this interview does contain spoilers as I wanted to ask Ragnar about some of the choices behind critical parts of Draugen’s story. If you haven’t yet played Draugen, or you want to remain spoiler-free, I recommend taking a few hours to run through it before coming back to this interview.

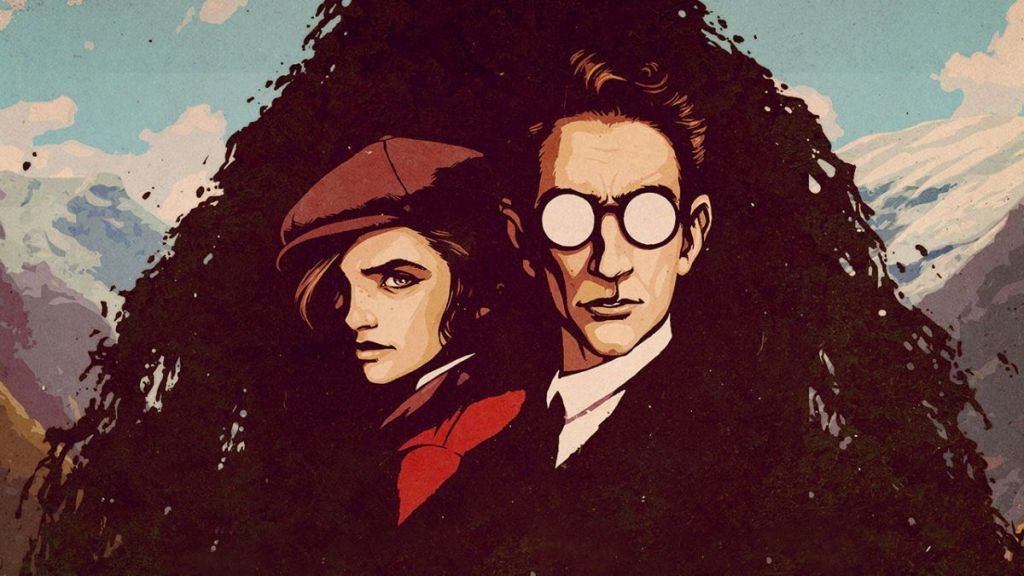

Here’s a picture of Lissie, staring down at all the spoilers waiting just below the boat.

PSLS: In Draugen, there are really two stories being told: one of Edward and one of Graavik. Did you formulate those two stories separately and then work to intertwine them, or were they always connected in some way?

Ragnar Tørnquist: Oh, they were always connected. They’re parallel and intertwined stories about isolation and desolation, both physical and metaphysical.

Without spoiling too much — although anyone reading this who hasn’t played the game yet: go play the game first! — there’s the lingering question of why Edward came to Graavik. We don’t spell it out, but there’s something there that pulled him to western Norway; perhaps Graavik needed Edward, and vice versa.

So, yeah, these two stories were always one story.

PSLS: Were there any deleted scenes, segments, or areas that were ultimately removed from the game? Why were those portions removed if so?

Tørnquist: Sure, that’s always the case with game development. We had ideas for locations that made it into earlier iterations of the game, but that were ultimately cut because they didn’t serve the story, or because the game changed along the way. All cuts were made before we created the final art, however, so there’s nothing hidden in the game or deleted scenes we can share with players.

PSLS: After completing the game, Draugen offers players the opportunity to read a short comic to add context to the story. What created the decision to separate these story beats out to the comic and flesh them out there?

Tørnquist: It’s important to say that the prequel comic is not required reading to understand the story, and also that reading it before playing the game will “ruin” a number of narrative twists. Which is why we unlock the comic book only after you’ve completed the game. Having said that, reading the comic first might actually bring a different perspective to the game — although you would need a friend to play through the game for you!

It wasn’t really a question of taking anything from the game and putting it in the comic book. Instead, there was so much history and backstory that’s referenced in the game that we wanted to explore…and instead of saving some of that for potential sequels, we decided to do something different.

Personally, I just wanted to dig deeper into the lives of Edward and Lissie and flesh out their relationship. In an earlier iteration of the game, you actually went back to Edward’s childhood and played some of those memories — in dream sequences — but we ultimately felt that this detracted from the main story. So we used them in the comic instead. The same goes for some of the scenes aboard the ocean liner. The game was originally intended to begin with a scene aboard the ship, but we changed that because it didn’t serve the story.

Rather than removing anything from the game, we took these missing pieces and brought them to life in a different medium. Which is something we like to do!

PSLS: Graavik is a remote area in Norway, while Edward and Lissie are Americans. What drove the decision to present that world and culture being explored from the perspective of an outsider? Is Draugen Graavik’s story, or is it Edward and Lissie’s story?

Tørnquist: Both! It’s hard to separate the two. Having said that, the heart and soul of the game is Lissie and Edward…though maybe not in that order. I can’t tell you which came first, the setting or the characters; they evolved organically, as one.

The setting — even to most Norwegians — is rather exotic, and it helps to see Graavik through the eyes of a stranger in a strange land. Edward represents the outsider, the tourist, observing and discovering a world that’s alien to him — just like most of the players. And even though he’s American, most players will probably, hopefully, embrace Edward’s point of view as their own. He voices what they cannot: the wonder and fear of being trapped in a remote community in western Norway in 1923.

PSLS: The game itself is an interactive playable delivery system for the narrative with very few puzzles or challenging gameplay elements aside from light exploration and collection. Did the game ever go through iterations of more or fewer gameplay mechanics, and how did you land on the existing gameplay and narrative delivery?

Tørnquist: Definitely — we had more puzzles along the way, but we always felt like they got in the way of the narrative and the mood. We constantly simplified the mechanics, based on both internal and external playtests, along with our own gut feelings. Draugen is a mood piece, a story, a portrait of two people and their relationship, and a setting that’s never been explored in a game. We didn’t want this to be a difficult game or a game that players would abandon because of complex puzzles or mechanics. Our goal was for everyone to be able to complete it.

PSLS: If there was anything more that you could do with the game, either adding something or changing some aspect of it, what would it be?

Tørnquist: To be honest…nothing much! That doesn’t mean we think it’s perfect, far from it. But Draugen was always meant to be a small, intimate, personal story. Adding more locations, more chapters, more characters — all of that would detract from the narrative.

As mentioned earlier, there were some scenes that were cut from the game, including flashbacks to Edward’s childhood and an opening scene on the ocean liner, but these scenes were cut for a reason. Bringing them back wouldn’t really serve the game or the story.

PSLS: Much of Draugen’s story is presented through spoken dialog, though a few key moments are shown (the blood where Ruth fell, the hanged man, Anna’s body in the bed, etc.). What made you decide what would be hidden behind spoken exposition and what would be shown to the player?

Tørnquist: We wanted as much of the story as possible to be told visually, through scenery and set design. Given that large parts of the story are about events that have already taken place, however, we also needed a way for Edward to discuss his discoveries and theories. This is why we spent so much development time on the dialogue system and the relationship between Edward and Lissie. We wanted their conversations to feel natural and unforced, and to reference what they, and the player, see and experience along the way.

Whether the show/tell balance in Draugen is perfectly weighted, I can’t say. But this is always on our minds and dictates many of the creative choices we make. At the end of the day, it comes down to what storytelling tools we have at our disposal. We decided early on to not have cut-scenes, which meant that we couldn’t really direct the camera or the player’s focus (although we do cheat on a couple of occasions). This also meant that we needed dialogue to communicate some of the more complex plot points.

Having said that, there’s a lot of story embedded in the world, and curious players will hopefully be rewarded with texture and depth.

PSLS: In the end, while Edward’s story gets more fully fleshed out, you let the player decide what happened to Ruth and the rest of the townsfolk in Graavik. Are there more clues along the way that point to one outcome or the other, or is it intentionally left vague and without a definitive conclusion?

Tørnquist: That’s a very appropriate question. While the critical reception has generally been very good, there have been a number of players and critics who didn’t like the open-ended nature of the narrative. And that’s absolutely fair: we knew this would be a point of contention. It was a conscious choice, and we stand by it.

There are clues in there, but those clues can be interpreted in many different ways — something that’s pointed out by Lissie towards the end of the game. Because it’s really not about what actually happened. It’s about why it happened, and what was rotten about this place that was so isolated and left behind by the rest of the world. And how that relates to Edward and Lissie. And Edward’s sister. And the idea of loss and trauma. And and and. (There are a lot of “ands” in this game.)

There’s a lot of “optional” information in the game that some players probably missed out on, and that information may help you make up your own mind about what happened — but, to be honest, we never wanted to spell it out. We specifically wanted players to form their own conclusions.

I have my own ideas about what actually happened, of course. But I’m not going to share those ideas, and I’m not even convinced that I’m right!

PSLS: Draugen has a few obvious themes, such as isolation and being alone, as well as some aspects of mental illness and coping with trauma. Are there any other underlying themes woven into the story that players might overlook?

Tørnquist: Those are the key themes: what isolation and loneliness does to a person and a community, and how we choose to deal with trauma and loss. And they are of course intertwined.

The keyword here is “haunting”, of course. Of being surrounded by ghosts, in many different forms. Ghosts represent loss and longing, memory and regret: Edward’s ghosts have taken physical shape, while the ghosts of Graavik live only (or mostly? There are unexplained events in the game that hint at something more) in letters and books and inscriptions.

And, of course, there’s still the question of Edward’s companions: what they are, where they came from, whether they’re mental constructs or something other. They haunt him, being haunted, being accompanied by ghosts — is that always a bad thing? “I’m never alone,” he says. How does Edward feel about that?

PSLS: The end of the credits promises that Edward and Lissie will return. Any hints on what adventures you plan to take the pair on next?

Tørnquist: We’re always thinking about where our stories may go next, and I’d love to do two more short games — or one longer one — that explores what happens directly after the end of Draugen.

If you’ve read the prequel comic, that might give some hints as to where we’d go next. We would, of course, dig deeper into the true nature of Lissie and the Entity, explore their origins and relationships with Edward.

Most importantly, any sequel or sequels would be tonally different from Draugen. The “red thread” (so to speak) would be Edward and Lissie and their bond, while the setting and the game mechanics would change to fit the new narratives.

Thank you to Rangnar for taking the time to talk to us. Draugen is available now on PS4, Xbox One, and Steam.