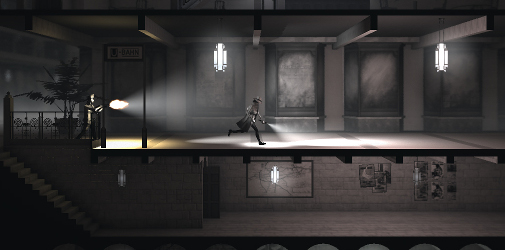

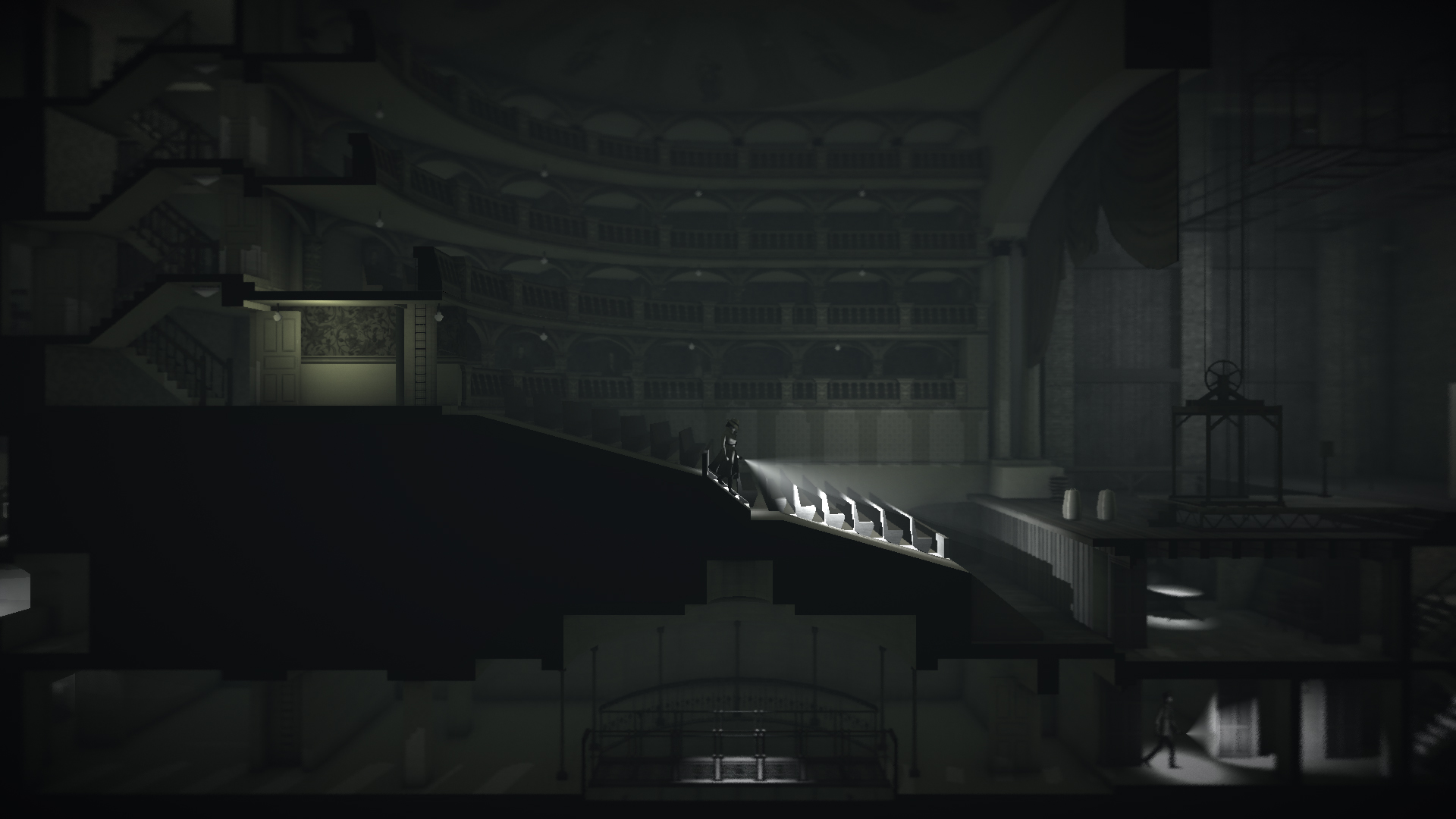

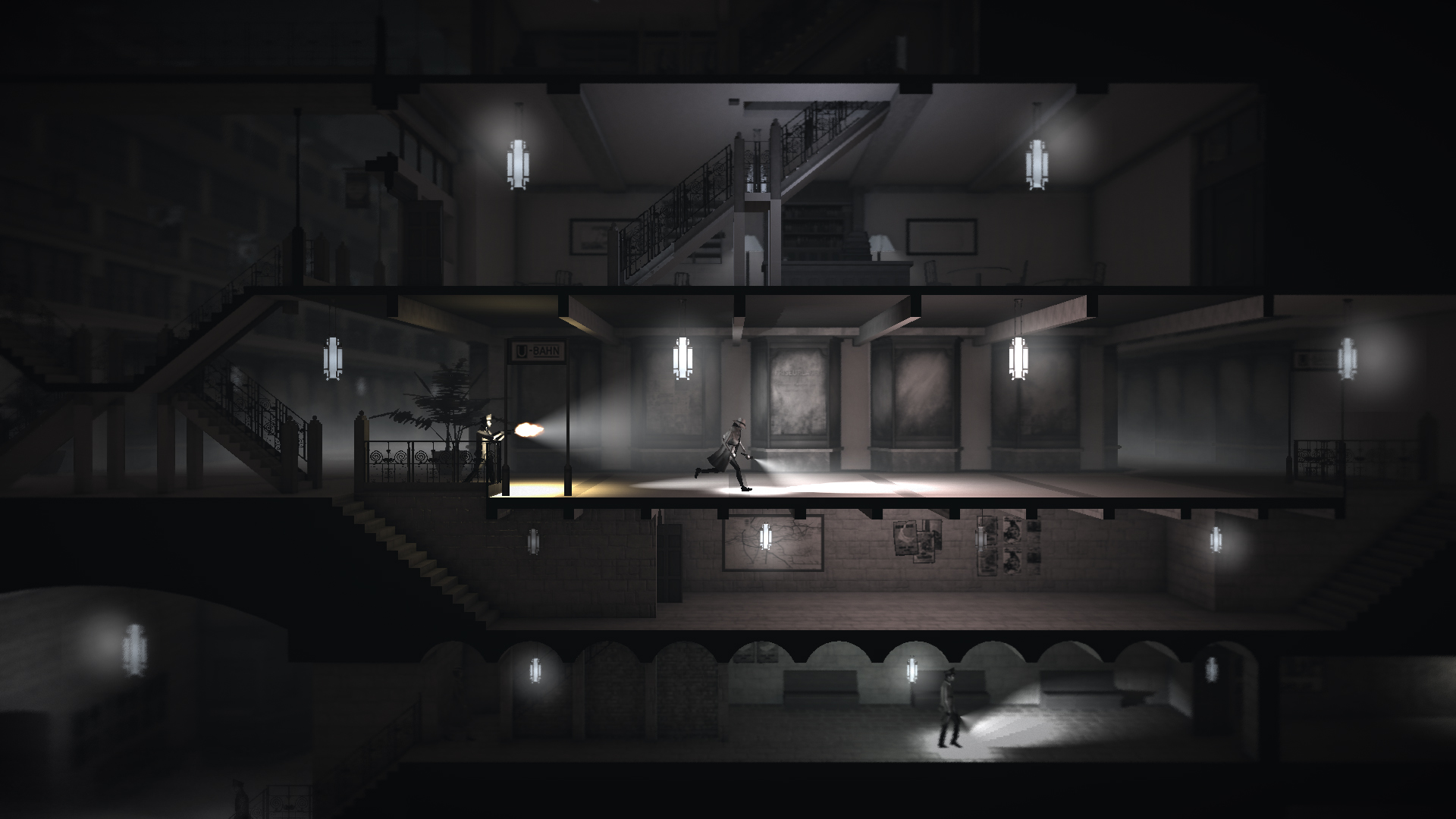

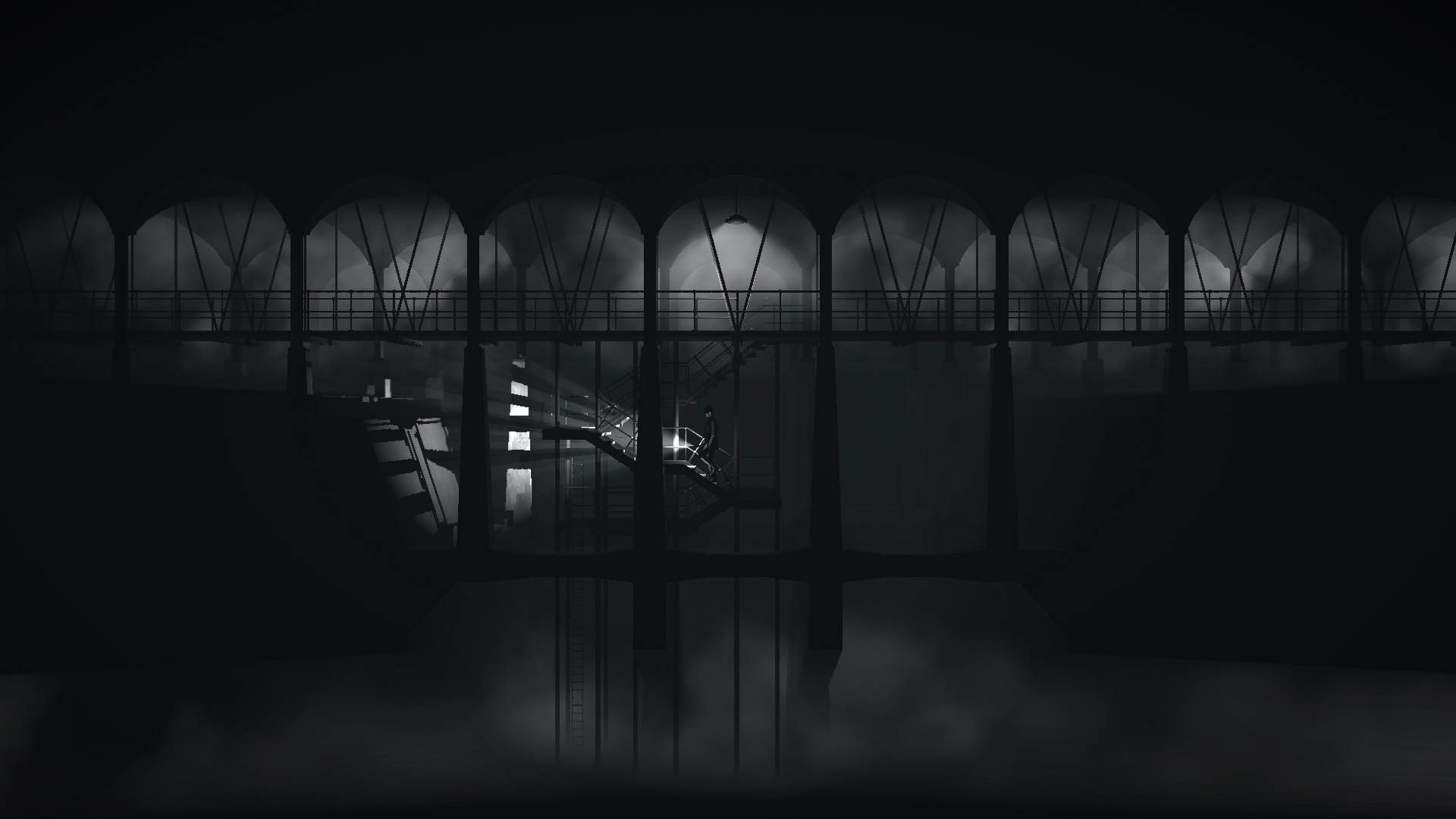

Calvino Noir is drenched in genre. Literally, it feels like it’s always raining in its city, coating it in a layer of grime that sticks to the characters. Lead man Wilt is a calmer Max Payne, written with the same gravely-yet-poetic monologues — some of which you can demand he make — only with an earnestness that works more often than not. He hates the city along with everyone else, at least it’s easy to understand that with the way the streets and buildings are drawn like ruins, in dull, grey and black shapes, highlighted with shafts of light. Wilt wears a trenchcoat and a fedora. Jazz plays on the opening screen. Calvino Noir couldn’t look and sound more noire if it tried.

Close but No Cigar

Style is one thing. L.A. Noire was one of the last big efforts to take the filmic aesthetic and try to meld it with a game about mystery and police work, but underneath the shadows and cigarette smoke was a frustrating sometimes-shooter-sometimes-adventure game. Since then, there’s been what feel like homages, rather than copies — which may be for the better. The Wolf Among Us doesn’t pull directly from the tropes of noire, but twists the style of it into something that works for a detective story about cynical, fairy tale creatures. It’s not completely about noire themes, it ends up being a game largely about about finding answers and success, but it earns several moments of melancholy and grit with the genre blanketing the strange and dark narrative.

Caught Off-Guard

Calvino Noir presents itself as a game that might fully imbue noire into its core. It’s a methodically-paced stealth game, where most of the time you have to be the lone figure standing in the darkness, the bright cone of a street lamp in the background tracing your figure. You wait, studying the guard patterns, their flashlights scanning up and down stairways and rooms. Then you creep towards the back of one of the armed men, a meter appears and fills with red, he flips around, and shoots. You die, your body disappears, the screen flashes and you’re back in the darkness, waiting for another moment to strike. After the twelfth or thirteenth death, the recreated noire look of Calvino Noir is a prison, sucked of its patience and rhythm.

Death wouldn’t be so bad if it wasn’t frequently unexpected. This is a stealth game remember, a genre that deals in giving you just enough clear, visual information about your presence in the world to make sneaking around a fair challenge. Guards probably have vision cones in Calvino Noir, except I have no sense of how wide or long they are. They probably have a sensitivity to the noise I make as I pass by, except I have no sense of how loud my steps are. There’s probably a reason you can choose to hide in the background of the 2.5D buildings, except I have no sense of how hidden I really am. Even after many, many deaths, the guards’ capability remains mostly unknown to me. Sometimes I can get behind them and choke them out, other times they are alerted and fire a shot off before my hands reach their throat. Combined with the game’s slow movement, slower climbing, and the requirement that you separately move multiple characters to the same point before continuing, makes for an often infuriating experience.

True Color

That kind of friction, the kind where every step could undo your five minutes of waiting, your narrow squeeze in between guard patrols, could be evocative of the narrative’s paranoia and corruption. The guards are all armed, as if they’re certain there will be an intruder. There could be a beauty to the oppression, the thrill of slipping out from under it. Instead, Calvino Noir, deals in arbitrary pass and fail modes. There’s no malleability to your path; you do what the game allows you to do, which is, by technical limitations or not, inconsistent. The simple act of walking is complicated by the game’s dual layered scenes. Characters can shift into the background to ascend stairs or ladders with an upward button press. The level of forgiveness in the control scheme here is minute. You will walk up stairs when you don’t intend to, you will walk by them when you do, and sometimes you just pace in front of them until a guard violently relieves you of your misery. Contextual actions like opening a door, looking through its keyhole, picking its lock, and observing an object in the scene, appear as icons as you search the environment. On the PlayStation 4 controller — not the PC version’s mouse controls, apparently — you must cycle through these until you highlight the right one, which becomes a primary cause of death when you’re trying to select the right cue as an enemy approaches. When this feature is responsive, it’s invisible, but most of the time it’s a larger threat than the guards themselves, making failure feel inevitable.

The system you rage against in Calvino Noir is not the muddy, corporate pressures of Wilt and crew’s dry story, it’s your own means of existence in the game itself. It’s really not about espionage, but a losing fight against your influence in the world. You have the ability to choke guards, to pick locks, to interact with certain objects based on what character you’re currently playing, however those abilities are not guaranteed, highlighted with laborious repetition. In that way, there’s a cynicism deep-rooted in Calvino Noir, a heavy darkness you can’t escape. Death is always lurking, success is futile. Maybe this is the best representation of noire in games that nobody wanted.

Calvino Noir review copy provided by publisher. For information on scoring, please read our Review Policy here.

-

Intricate devotion to film noir aesthetic

-

Gritty, self-serious monologues that you can choose to make

-

Bland plot

-

Infuriating control scheme

-

Inconsistent guard awareness

-

Punishing checkpoints

Calvino Noir Review

-

Calvinonoir1

-

Calvinonoir2

-

Calvinonoir3

-

Calvinonoire4

-

Calvinonoire5

-

Calvinonoire6