There’s a melting pot of great ideas in Past Cure. The setup presents a great mystery. Ian, a former soldier, is missing three years of his life and keeps having horrific nightmares. He also woke from those missing three years with telekinetic abilities, powers that at first he was unable to control. Now that he has a handle on his powers and his nightmares (by taking a blue pills that he’s been able to get his hands on), he and his brother are trying to figure out what happened in those three years.

Many clear influences and styles shine through during the length of Past Cure’s campaign. At times it seems like it wants to be Max Payne, and at others there’s an Evil Within or Silent Hill vibe. The opening moments even had me thinking Heavy Rain for a time, as they were presented in a very cinematic way. There are some clear signs that Past Cure is an indie game, but an impressive eye for art and graphic design, and a certain cinematic flair had me excited in the opening hours. Sadly, it never fully realizes any of its influences. A number of opportunities feel wasted as an intriguing mystery turns into a repetitive slog.

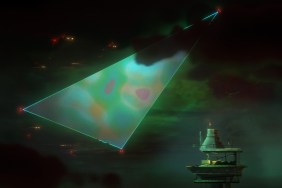

This is terrifying. Sadly, most of the game is not versus this. It’s versus generic grunts.Past Cure doesn’t nuance any of its ideas. Instead it balls them up like tightly packed snowballs and pelts me with them until I’m numb from the cold repetitiveness. After a long while, it would find a new element to latch onto, and the process would repeat. Most things aren’t presented as a nicely digestible meal. Ingredients seemed to be tossed at me one by one instead of mixed and blended. Here’s your cinematic mystery. Here’s your third-person shooting. Now do stealth. Now you’re in a nightmare. Ready for a boss fight? There are clear cut-and-dry divisions throughout the game that act as compartments for all of the ideas and influences that Phantom 8 must have had while making the game.

Box of Ideas

The opening of Past Cure acts as a tutorial, going back and forth between wandering Ian’s house picking up collectibles and living his nightmares. Every once in a while his nightmares seem to bleed outside of his sleep, with the creepy ceramic monsters seeming to appear in reflections and even fully manifest in his house. I was introduced to the sanity meter, which drained as Ian used his abilities. I was taught to shoot and fight hand-to-hand. I was interested. I was ready to dive in. Then the game stuck me in boring and repetitive gun fights in a parking garage for far too long.

The sanity meter doesn’t actually do anything, other than dictate when you can and can’t use your powers. At the outset, I had hoped it would be an interesting mechanic. I though it might be something like using your powers to help you win fights, but draining your sanity will make you see things that aren’t there and have other gameplay effects. It doesn’t. Draining sanity makes the screen blurry for a split second, and then it recharges to a point, which meant that slowing down time to pop out and shoot generic thugs in a parking garage (and hotel hallways and some random high-end living space) was never more than a simple approximation of a Max Payne game. And boy, did it wear itself out.

When Past Cure dives into the nightmare realm, it really starts to come into its own. Locked in a prison, Ian must find a way out while avoiding the gaze of horrifying ceramic-bodied humanoid creatures. This area has a few simple puzzles to overcome and a number of confusing hallways to traverse, but it’s far more varied and interesting than the shooting sections or the stealth hotel level. Instead of embracing the narrative and nightmares, it spends far too much time sending players down boring, repetitive, pre-cut pathways filled with generic grunts to gun down.

Discovering the secrets did keep me going though. Reaching the hotel suite led to a fun–if simple–investigation portion as I scoured various hotel rooms for clues, but immediately after, I was thrown into more gunfights in the same hallways that I had just come in from. The world is simply not interesting or varied enough to create a narrative of its own (unless you want to make up a story about why the hell people would park in a maze-like pattern in a parking garage). The game leans heavily on its narrative moments and upholding an interesting mystery in order to pull players through the rote and numbing action.

As intriguing as the story can be, the voice actors seem painfully uninterested in delivering their lines with the intended emotion and inflection that the script ought to call for. There were numerous places where I felt that my Google Assistant’s voice would do a better job at reading the lines than the voice actors did. Delivery often sounded like a high school play, where the actors were more focused on what was being said, and not how it was being said. While I won’t spoil it here, Past Cure’s ending does feel a little too ambiguous, never quite giving me the payoff that I was led to believe the mystery might lead up to. That seems to be a theme for much of the game, presentation of ideas that never quite payoff in the long run.

The Final Nightmare

Drudgery may have struck the rest of the game, but Past Cure’s final boss encounter is a fun battle that finally marries all of the elements the rest of the game never seems to tie together. Use of powers, weapons, and more dynamic mechanics than the entire rest of the game all play a role in the multi-stage encounter. It was a welcome fight, particularly after a shootout just prior against a boss that was a bullet-sponge test of patience (and an entire game’s worth of enemy waves in boring hallways. My bar wasn’t high). It’s a short game. Depending on how much you fight through unfair enemy waves, you can probably reach the end in four to five hours, and no Platinum trophy means little-to-no replayability.

Visually, the environments look very polished, though very simple and clean. That sterile feeling to the real world is what makes Ian’s nightmare world even more interesting. It’s messy. It’s falling apart, and it has a lot more details that actually tell a story. Past Cure has a very particular art style to it that is actually quite appealing from a graphic design perspective, and the cinematic camera really helps to highlight these sections. Character models, on the other hand, are lacking. From some distances and angles, enemies can look like they were ripped from Grand Theft Auto III (take a look at the list minute of my gameplay video at the top of the page). Main characters have a lot more polish put to them, but even then, they enter the uncanny valley.

Past Cure is an odd mash of Max Payne, The Evil Within, Heavy Rain, and a bit of Inception, without ever fully realizing any of those influences—compartmentalizing each section instead of creating a unique blend. Ideas teased early on never come into play, with nightmares and the real world staying largely separate from one another until the script calls on them not to be. An intriguing narrative is interrupted by long bouts of boring wave-based shooting against generic enemies in dull locations. I can’t help but think of the early moments in Ian’s house, seeing ceramic horrors in reflections and being excited for a cinematic psychological-horror action game that would never come to be.

Past Cure review code provided by developer. Version 1.02 reviewed on a standard PS4. For more information on scoring, please read our Review Policy.

-

The opening moments of the game

-

Fun final boss fight

-

Great cinematic and art design

-

Long boring shooting/stealth sections

-

Psychological horror rarely overlaps the third-person shooting

-

Voice acting misses emotional beats and inflection

-

Sets up too many ideas that never pay off, both in narrative and gameplay

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review

-

Past Cure Review